Black people have a long history of poor medical treatment – no wonder many are hesitant to take COVID vaccines

As the second wave of the pandemic sweeps through many countries, several COVID-19 vaccines are showing positive results in the final stages of testing. Governments are now racing to secure doses of these new vaccines for their citizens.

However, a significant portion of the population – in the UK and elsewhere – are hesitant about taking any of the new COVID-19 vaccines. This is particularly true of many Black people, despite being in the group most likely to die when infected with the virus in both the US and UK.

Various surveys in the US have shown that COVID vaccine hesitancy is significantly higher among Black people compared to white people. And a recent UK study has found that Black, Asian and minority ethnic people are nearly three times more likely to reject a COVID-19 vaccine for themselves and their children compared to white people.

The general antipathy towards vaccination is surprising, as vaccines – along with antibiotics – have been one of the most effective medical and public interventions over the last 100 years. Unfortunately, a series of mistakes, particularly around the early implementation of the polio vaccine in the 1950s, means the reputation of mass vaccination remains fragile, despite the very good recent safety record of vaccines.

Over the last 20 years, the situation has been exacerbated by the debunked and yet persistent associations between the MMR vaccine and autism. This has given momentum to current misinformation around vaccination, which is very difficult to control.

However, the scepticism of many Black people in the UK and US towards taking any new COVID-19 vaccine cannot be seen as just another anti-vaxxer response. It is the result of something far deeper. For Black people both in Africa and in other parts of the world, there is a long legacy of poor medical treatment and questionable practices in drug development, which has negatively impacted them for over a century.

Historically, one of the most renowned examples of medical mistreatment was by the doctor J Marion Sims in the mid-19th century. Sometimes referred to as “the father of gynaecology”, he used his position to experiment on enslaved Black women in the US, using unethical practices. Another example is the Tuskegee study that ran between 1932 and 1970, which was supposed to investigate syphilis treatment in Black men. Doctors involved left many men with the disease, even when effective treatment became available.

There is also the story of Henrietta Lacks and her family. As a cervical cancer patient, Lacks had cells taken from her before she died. These were subsequently used to study a variety of diseases. Once scientists realised the usefulness of her cells, they were shared widely around the world, along with her medical records and other information about her family and their genetics. Consent for using her cells was never sought. It was only in 2013 that the Lacks family gained some control over how the cells and their genetic information would be used in future.

Experience of poor healthcare

But vaccine hesitancy today might not only be inspired by historical events. Black people continue to be the victims of poor and neglectful treatment when they interact with medical services. Death from COVID-19 is possibly just the latest example.

There is extensive evidence to show that Black people are not receiving the same level of care in hospital settings as their white counterparts. The classic example is the reluctance of medical practitioners to give Black people pain medication for the same conditions as their white patients. And a key study in the US shows that over 50% of Black people perceive they have been discriminated against in hospital settings, with 43% believing they received poorer care. Most worrying is that 14% felt that doctors and nurses did not want to touch them.

Inequalities in healthcare are not restricted to the US, either. Recently, the Labour Party leader Keir Starmer reminded parliament that Black women in the UK are five times more likely to die during pregnancy than their white counterparts.

More widely, in Africa there have been serious concerns about informed consent and research practices in a number of clinical trials, including a current malaria vaccine trial run by the World Health Organization. One particular legal case – between the drug company Pfizer and the state of Kano in Nigeria over the testing of the meningitis drug Trovan – is credited with lowering trust in western medicine in the country, and potentially affecting the subsequent uptake of polio vaccines in the region.

The irony of the current situation is that this is the first time that the total economic and intellectual power of the western world has been so focused on a medical condition that disproportionately affects people of African and south Asian heritage. But if governments on both sides of the Atlantic want Black people to take the vaccine, they need to change the messaging – including not having government advisers saying that the impact of COVID-19 has nothing to do with structural racism.

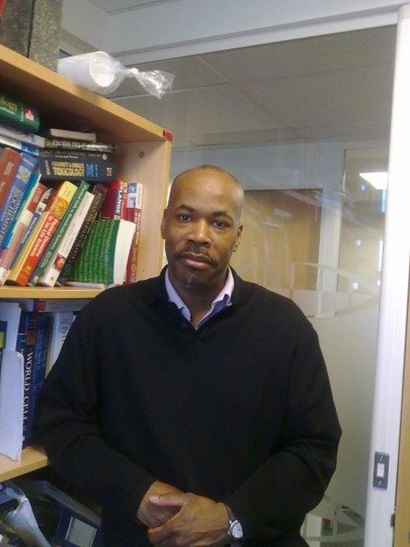

Likewise, the lack of trust from past events and current experiences can only be surmounted with the involvement of senior Black historians, scientists, doctors and public health professionals. They need to directly explain historic grievances to those running vaccination programmes, and then communicate clear messages about the COVID-19 vaccine to the Black community. Without their involvement, any mass vaccination programme is less likely to succeed.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.